Things are not what they seem

By Vicki Kellaway

In Colombia, sometimes your eyes deceive you. Even at some of the country’s most famous sites. This round up of popular destinations explains when sometimes things are not what they seem.

Salt Cathedral of Zipaquirá

The Salt Cathedral of Zipaquirá, which is 50km outside Bogotá, is not just one of Colombia’s most popular tourism destinations but also a place of pilgrimage – which is interesting considering it is not really a cathedral at all.

Although thousands of people have been known to attend the Sunday services at Zipaquirá, which is built inside the tunnels of a former salt mine, the Catholic Church doesn’t recognise it as a cathedral because it doesn’t have a Bishop.

Zipaquirá has undergone some deep transformations over the years. It was mined for salt, in one form or another, for more than 2,000 years and, as its productivity grew, its miners decided they would carve out a place to say prayers before work. The small sanctuary they created was expanded and developed into the first Salt Cathedral in the 1950s but, following a series of structural and safety problems, it was closed in 1990.

The current Salt Cathedral of Zipaquirá, beloved for its modern architecture and four columns representing the Evangelists, was built in its place and opened as recently as 1995.

The Islets of Guatapé

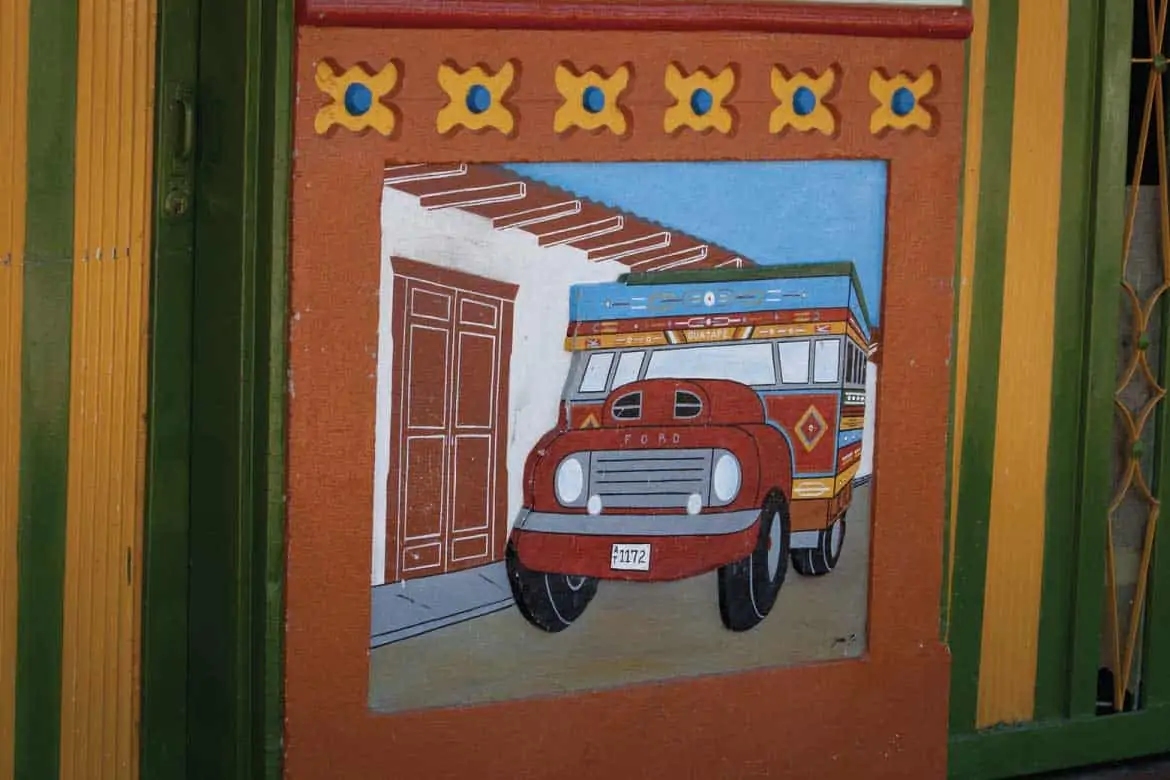

Guatapé, on the outskirts of Medellín, is an old Colombian town – founded by the Spanish in 1881 and thought to have been visited by the conquistadors as early as the 1550s.

The name was taken from the indigenous Quechua language and means something relating to ‘stones and water’. But there is more to this colourful town and its surrounding islets than meets the eye.

When viewed from the top of El Peñón de Guatapé (the 70-million-year-old Guatapé Rock nearby) Guatapé and its closest neighbours look like a series of small islands, scattered dots on an endless lake. But it’s not a lake at all, it’s a reservoir and entirely manufactured – the result of the Colombian Government flooding the valley to build a hydro-electric dam in the 1960s.

Isla Barú

One of the many reasons visitors love Cartagena is the colonial city’s proximity to the tropical dream of white sandy beaches drifting into the turquoise Caribbean Sea.

Thousands live that dream every year by jumping into the boats which line the city docks and heading across to Barú Island – except Barú, home of Playa Blanca, isn’t an island at all.

Isla Barú is in fact the end of a peninsula, a piece of land that stretches into the sea before curling back towards Cartagena – creating the false impression of an ‘island’ 40 minutes across the water.

It is separated from the city but only marginally, by the waters of the Canal del Dique – the 118km canal built to connect Cartagena’s bay to the Magdalena River. The Spanish built the canal in 1582 after discovering that the river was inaccessible directly from the sea.

However, after years of neglect and failed efforts at rebuilding, the Canal del Dique has become virtually unusable, although efforts are ongoing to restore it.

The Tatacoa Desert

The Tatacoa Desert is one of the widest open spaces in Colombia and is beloved for its distinctive yellow, grey and brown colours, its wide array of fossils and the brightness of the stars that shine above it at night.

The Spanish called the place Tatacoa, which refers to rattlesnakes, and snakes can be found there alongside turtles, scorpions, spiders, alligators and wildcats. Eagles are often seen flying overhead too.

But the Tatacoa Desert is not what it seems either. It’s not really a desert at all but, a tropical dry forest that has been slowly drying for centuries. The animals and plants which occupy its vast canyon-filled 330 square kilometres have been forced to adapt over the ages to its high temperatures and humidity.

Incidentally the word tatacoa is often used in Colombian slang (“Está como una tatacoa,”) to refer to a wife who is unhappy that her husband is arriving home late or drunk.

Guatavita Village

At first glance Guatavita appears just like any other Colombian village – bustling with restaurants, handicrafts and friendly faces. It has pretty plazas, government buildings and shops and is close to the legendary volcanic lake of El Dorado – which was famously a deposit for gold and other offerings during long-ago indigenous ceremonies.

But Guatavita is not the original village. It’s a replica. The entire town and its people were relocated by the authorities in 1967 – again after a Government flooding programme.

The old village became a large reservoir, designed to provide water to the citizens of Bogotá and surrounding areas and also to regulate flooding on the savannah. The Government began building the new village in November 1964 and moved everyone three years later. Residents joke that on a clear day they can still see the top of their old church poking above the water.

Eje Ambiental

The Eje Ambiental in central Bogotá is designed to bring greenery and a sense of nature to an otherwise bustling part of the city. At its heart is a man-made, ornamental stretch of water that was in part designed by Colombia’s most famous architect Rogelio Salmona, a prize-winning architect who was himself the prodigy of Le Corbusier, a Swiss architect considered to be the pioneer of modern architecture.

But some things are not as fake as you might think. This gentle stretch of water, which slopes through the city in a layered, concrete spiral, used to be a real river – the Río San Francisco. Indigenous people originally called it the Vicachá River – which means the Night Glow – and it was at one time the largest river in the region, large enough to provide water to the entire city.

The name only changed when Franciscan monks arrived in the 16th century and built San Francisco church on the north bank of the river, changing the river’s name to match. The river was first channelled in the 1930’s and gradually reduced in size and strength.

The Colombian Way © 2017

About the writer

Brit Vicki Kellaway earned her stripes as a journalist back in the UK and has now chosen to make a life for herself in Colombia’s capital Bogotá.

Vicki is a regularly published contributor to Bogotá’s The City Paper and is also the wordsmith behind the award winning weblog Banana Skin Flip Flops where she chronicles her travels and insightful musings not only in Colombia but throughout Latin America

Of course, Vicki also writes exclusive articles for Colombian Life. Our online magazine.